Responding to the Call of Things

A Conversational Approach to 3D Animation Software

3. Things themselves

A phenomenon can be defined as “what appears” (H. Spiegelberg, 1971, p. 684) and, since the 1970s, much computer graphics research has aimed to simulate the way that phenomena appear to a camera (Bolter & Grusin, 2000, p. 28; Catmull, 2014, p. 14; Manovich, 2001, p. 180).

Phenomenologist philosophers, on the other hand, are interested in how phenomena appear to a living person, and it turns out that this question is far more complex because, unlike a camera, a living being never perceives reality in a detached or “objective” way.

Edmund Husserl is considered the father of phenomenology and it is from him that we get the slogan “back to the ‘things themselves’” (Husserl, 2001, p. 168). This slogan is urging us to get below distorting categories imposed by the intellect in order to notice and describe things as we actually experience them. Husserl’s early work suggests that, with careful attention, we can describe our experience of something without distorting it.

Heidegger and fellow phenomenologist philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, however, insist that acts of description and acts of understanding are always acts of interpretation. They emphasise that before we have explicit awareness of a thing (before we can start describing it), it has already been revealed to us in a particular way; Heidegger emphasises the role of language in this revelation and Merleau-Ponty emphasises the role of the body.

As proposed by Husserl at its inception, phenomenology was to be a systematic and exact science, but later proponents (including Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty) realised that it could never be an exact science and its value is as a “manner or style of thinking” (Merleau-Ponty, 2002, p. viii). As a style of thinking, phenomenology requires us to ask ourselves “what is it like?” and, without imposing an answer, we need to let things speak for themselves. But what are the things themselves and how can we allow them to “speak”? How can we hear what they have to say? Husserl, Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty each imply different answers to this question.

I am interested in the phenomenologist philosophers for what they can offer my project, which aims develop approaches to 3D animation that avoid reductive frameworks.

In this section I look at their work for suggestions about what strategies or methods might encourage an actively receptive comportment.

Objects and things

In “The Question Concerning Technology” Heidegger explicitly states that the essence of modern technology (as Enframing) is “nothing technological” (Heidegger, 1977, p. 20), suggesting that our approach to technology is more important than the particular technological devices that we use. Heidegger wants us to recognise Enframing as a particular mode of revealing, which means recognising it as a particular way of understanding (or revealing) the world.

A mode of revealing is a particular comportment or a sensibility, and Enframing is a reductive mode of revealing characterised by a challenging-forth which reduces things to standing-reserve (Heidegger, 1977, p. 17). I suggested above that there are similarities between standard 3D animation practices and Heidegger’s notion of Enframing. I used, as an example, Default Whippet. This project involved standard 3D animation practices which feel different from activities such as painting or drawing.

While drawing Ginger in the park I was sitting on the grass; she was doing her thing (i.e. sniffing around) and I was observing her as I sketched. But my comportment toward Ginger dramatically changed once I started using 3D software. Prompted by workflow requirements, I physically manipulated her into a “relaxed pose” (Figure 3.1), after which I dismissed her altogether, preferring to refer to easily accessible digital files.

While working in 3D, my focus was on achieving predictable and repeatable results and I dismissed a number of surprising (yet intriguing) images as mistakes. In accordance with the standard 3D character workflow, I exercised control over the dog and over the software. The resulting dog mesh is standing-reserve: standing by ready for use in other 3D projects and ready to be shared or sold on the internet.

The software itself is also reduced to standing-reserve, because I stick to standard procedures and only appreciate outcomes that are explicitly intentional and repeatable; I am not open and responsive to images that I didn’t (at least partially) conceive of in advance.

Finally, as a proficient user, who correctly implements the character animation workflow in a manner interchangeable with other proficient users, it seems that I have also become standing-reserve; valuable as a human resource for the animation industry.

Is it possible to use 3D software and still be open and responsive to Ginger as a particular and peculiar dog? And how can I be open to surprises that the software has to offer? In short:

How can I use 3D software without reducing things, such as the software, the dog and even myself, to standing-reserve? In other words, how can I avoid reducing things to objects?

In everyday speech, we often use the words thing and object interchangeably, but in Heidegger’s work these words have different connotations. In his book Heidegger Explained, Harman succinctly explains that “generally speaking, ‘thing’ is a good term for Heidegger and ‘object’ a bad one” (Harman, 2009, p. 8). For Heidegger the word “object” has negative connotations because it suggests something present-at-hand, consciously studied and reduced to a set of attributes. The word “thing”, on the other hand, has positive connotations and suggests a certain respect; a recognition that a thing’s “thingliness” ensures that it will never be exhausted or fully disclosed. For Heidegger, even the simplest thing could never be fully disclosed or fully intelligible, but reducing things to objects is a way of forgetting this fact. Harman could be talking about 3D computer graphics rather than science when he says that for Heidegger, “science reduces the thing to a present-at-hand caricature by replacing it with a set of tangible properties through which it is modelled” (Harman, 2009, p. 8).

My research is concerned with everyday physical things, as well as digital things including 3D software and 3D images and animations. The aim of my research is to explore ways of working with these things without entirely reducing them to objects.

Being present to things

In the opening pages of his essay “The Origin of the Work of Art”, Heidegger argues against our commonly held belief that a thing is the bearer of its characteristics (or traits) (Heidegger, 2002, p. 7). He finds that this definition of a thing is lacking because it doesn’t fit with our experience of things. He says that:

Prior to all reflection, to be attentively present in the domain of things tells us that this concept of the thing [as bearer of traits] is inadequate to its thingliness, its self-sustaining and self-containing nature. From time to time one has the feeling that violence has been done to the thingliness of the thing and that thinking had something to do with it. (Martin Heidegger, 2002, p. 7)

A thing’s “self-sustaining and self-containing nature” (Martin Heidegger, 2002, p. 7), its thingliness, ensures that it always has more in reserve and always has the capacity to surprise us.

Heidegger’s description of violence being done to the thingliness of the thing resonates with my experience of making Default Whippet, where a type of violence was done to the thingliness of Ginger, the thingliness of the software and perhaps to the thingliness of the animated work.

Heidegger suggests that when we consciously study a thing by pulling it apart (physically or conceptually) and measuring it, the thing becomes present-at-hand and it is reduced to standing-reserve. He goes on to say that, when it comes to being attentively present to things, feeling or mood can be more perceptive and “more open to being” than calculation or “reason” (Martin Heidegger, 2002, p. 7). Through the use of a modular workflow, studying things as component parts and working with digital images, feeling and mood played little role in the production of Default Whippet.

My concern with fulfilling workflow requirements and achieving accurate results meant that I wasn’t attentively present to things constituting the practice situation; to Ginger, to the software or to the work.

The thingliness of digital objects

According to contemporary author and a computer scientist Jaaron Lanier, a digital object is always designed for a particular purpose. In his book You are not a Gadget, he explains that “there is no such thing as a digital object that isn’t specialized” (Lanier, 2011, p. 133). He insists that if we assume that a digital object entirely stands in for what it represents then we “believe in bits too much” (Lanier, 2011, p. 133). To illustrate this point, he gives the example of a jpeg image (a digital file or digital object) which represents an oil painting. Given this example, we can see what Lanier means because an oil painting obviously has qualities that a jpeg image doesn’t have. However, it is equally true that a jpeg image has qualities that an oil painting doesn’t have, and the question is whether we miss something about the jpeg image if we think of it merely as a representation of an oil painting. In other words:

do we miss qualities inherent in digital objects if we encounter them only as they were designed to be encountered?

The danger of believing in bits too much is that we reduce physical objects and processes to digital representations, i.e. we reduce things of inexhaustible complexity to simplistic caricatures. But not believing in bits enough means conceiving of digital objects as bearers of a quantifiable set of traits, and this could be an equally reductive move. Approaching a digital object (such as a 3D animation package, a tool within that package or the 3D animation produced) solely in accordance with the purposes for which it was designed might be another way of doing violence to the thingliness of a thing. Glitch artists such as Menkman appreciate the capacity for digital media to consistently surprise, and innovative 3D animators such as Hilleli and O’Reilley continue to develop practices that are not listed in the help menu and are not anticipated by software designers. These digital artists respond to qualities inherent in digital objects and these are qualities which have not always been put there by design. In the next section I describe a practical enquiry which explores the thingliness of digital objects and asks whether qualities inherent in digital objects are inexhaustible. Does 3D software have the capacity to continually surprise?

Beginning in poverty

Heidegger suggests that when we consciously study things they become present-at-hand (like the broken hammer) and are reduced to standing-reserve. He emphasises that things themselves are essentially withdrawn, and suggests that we learn more about things by using them rather than consciously studying them (Heidegger, 1962, p. 99). But, for Husserl, the things themselves are things explicitly examined and consciously experienced. Husserl’s writings include detailed descriptions of isolated objects such as a white piece of paper (Moran, 2000, p. 153), a mailbox (Harman, 2002, p. 131) or an inkpot on his desk (Husserl & Welton, 1999, pp. 52–53). For Heidegger, Husserl’s phenomenological studies are contrived experiences because normally we interact with things without explicit awareness of them. Husserl is interested in conscious experience but for Heidegger conscious experience is always secondary and arises from an unnoticed, pre-theoretical background.

By carefully describing the perceptual phenomena associated with his inkpot, Husserl becomes a subject (a conscious observer) knowing an object (the inkwell), and Heidegger insists that we don’t normally experience ourselves as subjects standing back and assessing objects. Just as a normal day might find Newell anticipating the taste of tea rather than focused on the shape of his teapot, on a normal day at his writing desk, Husserl would use his inkpot without explicit awareness of it at all. On these days his relationship with the inkpot is one of practical involvement or “equipmentality” which, as Thomson explains, is a relationship where subject and object have not yet been differentiated and things are not yet entities with objective properties (Thomson, 2011, p. 82) .

The previous section described Heidegger’s notion of “equipmentality” in terms of a ready-to-hand hammer in use and a present-at-hand broken hammer. It’s important to recognise that Heidegger’s description of “equipmentality” isn’t just about tools; ready-to-hand and present-at-hand (withdrawn and revealed) are two basic modes of being that belong to all entities (Harman, 2002, 2009).

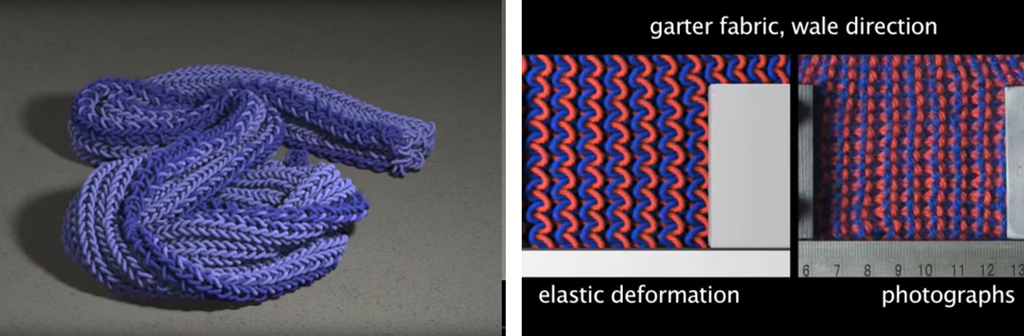

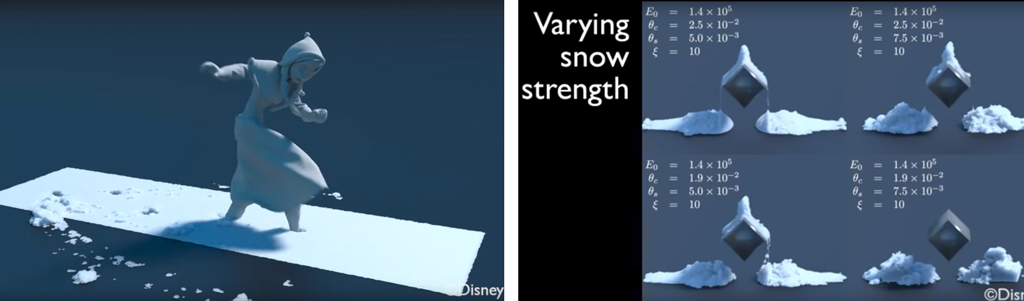

Despite Heidegger’s critique, Husserl’s phenomenological methods are of interest to 3D users because they represent an attempt to study the appearance of something in a manner free from theoretical explanations and common sense assumptions. Husserl calls his phenomenological method the reduction (Husserl & Welton, 1999, p. 67) or epoche (Husserl & Welton, 1999, p. 374), and it requires us to carefully describe what appears without referring to theories or explanations of that appearance. For example, a phenomenological description of hearing a siren should refrain from talking about sound waves vibrating the eardrum. For 3D users this is an interesting exercise because the tools that we use to describe things often seem to explain them as well. For example, there are algorithmic models which seem to explain how trees grow (Lindenmayer & Prusinkiewicz, 2004), how cloth behaves (Kaldor, James, & Marschner, 2008; Yuksel et al., 2012) and how birds fly in a flock (Reynolds, 1999; Reynolds, 1987). And at the heart of 3D software are a variety of complex algorithms which seem to describe how objects reduce in perspective, how light rays are projected onto the retina and how shading and shadows work.

3D software is comprised of computer algorithms which not only simulate the look of things, but also simulate the way that things behave (see e.g. Figures 3.2 and 3.3).

Given the intimate relation between description and explanation in 3D software, how can a user study the appearance of something in a manner free from explanation and assumption?

Forgetting the objects before you

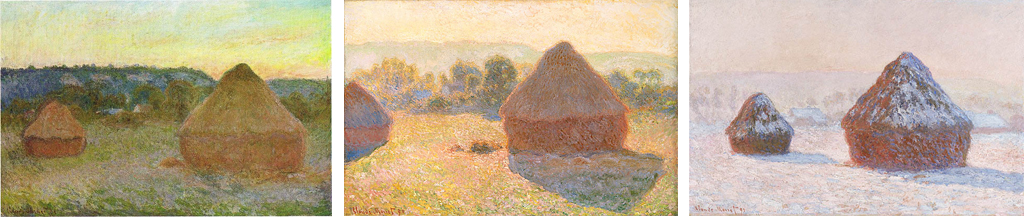

According to art historian John Gage, it is the Impressionist painters of the 19 th century “who first seemed to paint simply what they saw” (Gage, 1999, p. 209). In his book Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction, Gage quotes Claude Monet, a founder of the Impressionist painting movement, who gives the following advice to a fellow artist:

When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact colour and shape, until it gives your own naive impression of the scene before you [Emphasis added]. (Gage, 1999, p. 209)

Monet’s words suggest that there are similarities between the Impressionist approach to landscape painting and Husserl’s epoche. Husserl’s method aims to describe phenomena in words while Monet’s method describes perceptual phenomena in paint; both are careful studies of appearance, both bracket questions of existence and both aim to forget the meaning behind the phenomena being studied.

Accidents and essences

According to Graham Harman, the significance of Husserl’s work is his discovery of a gulf between things (or objects, as Harman prefers to call them) and their qualities. Husserl’s phenomenological enquiries reveal that the thing I am conscious of (and consciousness is always consciousness of something) persists below its accidental mode of appearance. An example of this is the way that I experience a unified thing (such as a dog, a car or a teapot) which remains constant despite a retinal image consisting of shapes and colours which change in accordance with changing lighting conditions and angle of view. What I see also changes according to shifts in my attention, mindset or mood.

Harman explains that “The trees and blackbirds we encounter are not detailed presentations of specific bundles of qualities before the mind. Instead, intentional objects have a unified essential core surrounded by a swirling surface of accidents” (Harman, 2010, p. 20). In other words, we normally just see a tree or a blackbird, not its shifting silhouette, its specular highlights or the shape of a shadow across its surface. We normally see through the swirling surface of accidents to unified things, but it’s interesting to note that it’s this swirling surface that intrigues many painters (including Monet).

Husserl wants to uncover the structures of consciousness (Moran, 2000, p. 153). In other words, he wants to find out what makes an experienced thing what it is. For this he needs to know which features of a thing are essential and which are accidental. He needs to know which features can be removed or altered without changing the identity of a thing. Therefore, in addition to bracketing the natural attitude, Husserl’s phenomenological method requires that we train ourselves to see essences by stripping away accidental qualities and surface noise. He calls this method the “eidetic reduction” (Husserl & Welton, 1999, p. 326) and it involves a thought experiment that incrementally strips things of their qualities while testing whether the thing still persists. Husserl assumes that this method will allow us to uncover the essential qualities of things. Natalie Depraz describes the eidetic reduction as “the procedure of discrimination between the intrinsic properties of an object (an armchair necessarily has ‘arms’) and its contingent ones (an armchair is not necessarily made of wood)” (Depraz, n.d.). Husserl’s aim is to see essences and to “fix” them conceptually, then linguistically (Moran, 2000, p. 134). To create 3D tools, programmers also learn to see essences; they need to fix them conceptually and then algorithmically.

For example, in the design of a mesh creation tool such as a Paint Effects tree for Maya (Figure 3.5 and Figure 1.15, above), decisions have to be made about which features of a tree are essential and which are accidental. In other words, the tool’s programmer or designer needs to decide what are the intrinsic properties of a tree (a tree necessarily has a trunk and leaves) and which are its contingent ones (leaves are not necessarily green – they might be yellow or red). Creating a 3D tool (such as Paint Effects tree) involves the definition of eternal or fixed qualities that are transferrable across states and situations of use and, if we investigate the code used to build such a tool, we find the notion of essences replicated on a more detailed level because 3D animation software embraces a development paradigm called Object Oriented Programming.

Object Oriented Programming

Object Oriented Programming (OOP) was introduced in the 1960s and has been the dominant programming paradigm since the late 1980s (O’Regan, 2008, p. 88).

The traditional view of programming sees it as a list of instructions to be performed by a computer. In contrast to this approach, OOP views a computer program as a collection of objects that act on each other (O’Regan, 2008, p. 87). Traditional languages keep code and data separate but, with OOP, code and data are combined within a code “object”. As O’Regan explains, “Each object is capable of receiving messages, processing data, and sending messages to other objects. That is, each object may be viewed as an independent entity or actor with a distinct role of responsibility.” (O’Regan, 2008, p. 87)

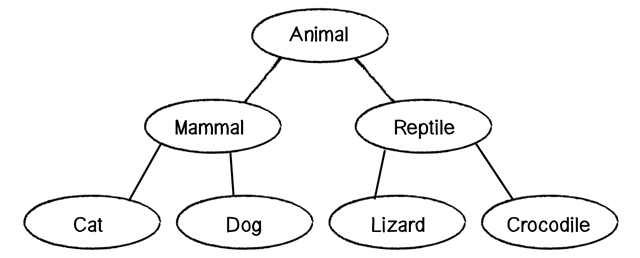

One of the tasks facing an Object Oriented programmer is to write code that defines a class. A class is like a recipe or a blueprint for the creation of an object. In OOP, an object is an instance of a class with its own particular mix of characteristics. For example, a class called “Dog” will define the attributes and behaviours for all possible dog objects. As the programmer who defines the Dog class, I decide what features are essential to a dog object and I decide which of these features can be varied by the user. For example, I may decide that breed, colour, size and number of legs are all attributes that can be varied without destroying a dog’s essential nature. A user of my Dog class can then create a dog object and input values for each of these attributes. One dog object might be a small black Kelpie with 4 legs and another might be a large purple Poodle with 3 legs. Reminiscent of Husserl’s eidetic reduction, the notion of essences pervades the construction of 3D computer software. As illustrated in Figure 3.6, another feature of OOP is inheritance, which means that a class can acquire the properties of another class. For example, a Dog class might be derived from (and inherit attributes from) a parent class called Mammal which might, in turn, inherit attributes from Animal.

Husserl died in 1938, long before the introduction of OOP and the development of 3D animation software, but I wonder how he would regard practices related to these technologies and whether he would consider these practices consistent with his phenomenological method. As it resembles the eidetic reduction, Husserl may find the process of creating 3D tools or defining classes to be useful activities but, as predesigned digital objects, what would he think of using these tools? In Cartesian Meditations, Husserl writes that the phenomenologist must “begin in absolute poverty, with an absolute lack of knowledge” (Husserl, 1982, p. 2). Given this assertion, we can assume that Husserl would not approve of using a Paint Effects tree because too many decisions about what constitutes our experience of a tree have already been made.

Given that there is so much knowledge embedded in Object Oriented computer software, it’s probably impossible for a 3D animator to begin in absolute poverty. But what would happen if we tried?

Wonder in the face of the world

Husserl asks us to bracket the existence of the world and forget the meaning of things so that we can focus on describing appearance. Merleau-Ponty, like Heidegger, insists that this is an impossible task because we could never entirely remove ourselves from the meaningful world. Merleau-Ponty thinks that the value of Husserl’s phenomenological reduction is that it teaches us “the impossibility of a complete reduction” (Merleau-Ponty, 1996, p. xv). He adds that the “best formulation of the reduction is probably given by Eugen Fink, Husserl’s assistant, when he spoke of ‘wonder’ in the face of the world” (Merleau-Ponty, 1996, p. xv).

We cannot remove ourselves from the world but we can slacken “the intentional threads which attach us to the world and thus bring them to our notice” (Merleau-Ponty, 1996, p. xv). In other words, we can never entirely forget the meaning of things but we can “break with familiarity” in order to notice “the unmotivated upsurge of the world” (Merleau-Ponty, 1996, p. xv). It seems to me that this is what Monet is doing when he sits in front of a haystack and tries to forget what it is that he’s painting.

Like many painters, Monet has trained himself to see accidental surface qualities instead of meaningful things. In a sense Monet turns himself into a camera and paints light hitting the retina but, while painting outdoors in front of a haystack, how detached can Monet really be? It takes work to stay detached and Monet is always pulled back in. Noticing a rustle of hay while he works he surely sees a home for rats, not streaks of colour. He can’t entirely detach himself from the meaningful world, but Monet can slacken intentional threads and get a sideways look at ordinary experience.

Monet has taught himself to see the swirling surface of accidents, but he is also interested in the moment that pieces of paint on a canvas become a haystack. Likewise, Newell (see above) might have been interested in the moment when Bezier curves become a teapot, but for those of us using this off-the-shelf mesh 40 years later, that moment is long forgotten.

Merleau-Ponty feels a particular affinity with the work of Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, whose project, as he sees it, is the same as his own. In his 1945 essay “Cézanne’s Doubt”, Merleau-Ponty explains that Cézanne’s work explores “primordial” perception (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 64). This means that Cézanne doesn’t succumb to the perceptual habit of seeing an already constituted or known and categorised world (as classical painters did according to Merleau-Ponty) and neither does he paint pure sensation (as Impressionists such as Monet supposedly did). Instead, Cézanne pursues an “exact study of appearances” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 61), but this isn’t as simple as it sounds because appearance doesn’t correspond with light hitting the retina. According to Merleau-Ponty, Cézanne abandons himself “to chaos of sensation” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 63). But he doesn’t paint pure sensation: instead he paints the world as it acquires meaning on the level of body and of the intellect.

Objects in the act of appearing

In accordance with Husserl’s suggestion that we should begin in poverty, Cézanne (like Franck) isn’t content to use established painting conventions, such as laws of composition or pictorial perspective, which were popular among many of his contemporaries: instead he struggles to describe perceptual experience which is dynamic, ambiguous and elusive. According to Merleau-Ponty, the apparent futility of Cézanne’s struggle prompted one of his contemporaries to remark that he pursues reality while denying himself the means by which to achieve it (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 63). By “remaining faithful to the phenomena”, Cézanne eventually develops “lived perspective” which is a looser version of the strict mathematical perspective used by his contemporaries (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 64). Taken in the context of the whole, Cézanne’s “perspectival distortions are no longer visible in their own right, but rather contribute, as they do in natural vision, to the impression of an emerging order, an object in the act of appearing, organizing itself before our eyes” [emphasis added] (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 65).

It’s interesting to note that, although Cézanne’s paintings are still images, they feel more dynamic than many 3D animations, which seem somehow static and stable by comparison. Perhaps this is because, in many 3D animations, the objects have already appeared, i.e. things have been objectified.

Following Cézanne, how could a 3D animator describe objects in the act of appearing?

According to Merleau-Ponty, techniques employed by the Impressionists end up dissolving objects. He prefers Cézanne’s technique of modulating colour because it returns the solidity to objects (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 62). He also likes the way that Cézanne describes things using multiple outlines because “To trace just a single outline sacrifices depth – that is, the dimension in which the thing is presented not as spread out before us but as an inexhaustible reality full of reserves” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 65). As 3D users, we work with a virtual third dimension and we are obsessed with depth which, for us, means the distance from a virtual camera. In 3D animation, distance is represented using automatic perspective projection, which can be accentuated by applying “depth of field” effects (Beane, 2012, p. 125; Derakhshani, 2013, p. 569; see Figure 3.9). But the illusion of spatial distance is not the type of depth that Merleau-Ponty is referring to: what he is referring to might be better described as allusion; it’s more like a hint or suggestion of something that is not entirely present.

The world of perception

Husserl’s methods enquire into things that we are explicitly aware of, but Merleau-Ponty (like Heidegger) emphasises that before we can have explicit awareness of a thing, it has already been revealed to us in a particular way.

For Merleau-Ponty the level of our primary revelation of the world is perception, and much of his work examines the phenomenology of perception. Rather than a scientific or biological explanation of our perceptual system (which might talk about light rays bouncing off objects and forming an image on the retina), Merleau-Ponty is interested in our perceptual experience as embodied beings.

Through an exhaustive investigation, Merleau-Ponty concludes that perception is not the construction (or projection) of a world by our intellect, nor is it the passive uptake of data about a pre-existing external world. He attributes each of these extreme accounts of perception to “intellectualist” and “empiricists” (Merleau-Ponty, 2002, p. 30)(T. Carman, 2005, p. 50). For Merleau-Ponty, neither of these positions can account for the richness and complexity of lived perceptual experience; his work takes a kind of middle road between these two extremes.

Merleau-Ponty insists that we exist both as conscious subjects in a world of meaning and as finite, embodied beings. For Merleau-Ponty, perception is always “value-added”; it is expressive, it stylises, filters and attributes meaning.

According to Merleau-Ponty (1963, p. 167), one of the many phenomena which show how perception is always already meaningful includes the way that we have trouble treating a face like a thing.

Through an examination of perceptual experience, Merleau-Ponty notices that what we see is largely based on the physical activities that we are able to perform. For example, he describes how distance and movement on a vertical plane (i.e. up and down) is different from movement on a horizontal plane (i.e. side to side). This is because, as embodied human beings, we have a front and a back and a top and a bottom. For perception, space is not neutral; it’s not like an empty container where each point or location is equivalent to any other. Instead, space “consists of different regions and has certain privileged directions; these are closely related to our distinctive bodily features and our situation as beings thrown into the world” (Merleau-Ponty, 2004, p. 67). 3D animation software is primarily based on the Cartesian coordinate system and it represents virtual space in mathematical terms. As a user of this software, there are a number of practices (e.g. building objects out of context and assembling a scene from component parts) that make it easy to assume that space is neutral.

Working within mathematically described space is one of several ways that standard 3D workflows allow the role of the body in perception to be hidden from view.

As an embodied being, my perception is based on my biology (e.g. eyes on each side of my head would reveal a different world) and it is also based on my culture and personal experience. Like many other humans (with bodies like mine), it’s difficult for me to treat a face like a thing and, similarly it’s difficult for me to see a dog in the same way that I see an inanimate object. When it comes to my own dog, Ginger, it’s difficult for me to see her like any other dog (or even like any other whippet). In Default Whippet I approached Ginger as though she were any other dog and (to a certain extent) like she was any other object. In this project my relationship with Ginger (including our physical proximity and our emotional bond) doesn’t come into play. For Merleau-Ponty this omission means overlooking the phenomenology of perception; and Heidegger, as we’ve seen earlier, suggests that it is a way of doing violence to a thing.

As 3D animators, how can we allow our (physical and emotional) relationships with things to influence our practice?

The arbitration of conflict

The dominant rhetoric surrounding the development and use of photorealistic rendering algorithms and NPR techniques reflects an assumption that there are some ways of representing the world that are “realistic” (Kozbelt, 2006) or objectively accurate, while there are others which are stylised, “expressive” or artistic (Power, 2009) – but Merleau-Ponty rejects this distinction.

For example, we might assume that images with mathematically perfect perspective provide an objectively accurate representation of the way the world is, and that deviations from this precision are stylistic interpretations. But, according to Merleau-Ponty, perspective is not a “technique of imitation”, it is the “invention of a world” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 86).

In his article on aesthetics, “Indirect Language and the Voices of Silence”, Merleau-Ponty writes:

It is clear that the classical perspective is only one of the ways that humanity has invented for projecting the perceived world before itself, and not the copy of that world. The classical perspective is an optional interpretation of spontaneous vision (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 86).

For Bolter and Grusin (2000, p. 25), the relevance of pictorial perspective is that it helps to dissolve the surface of a picture and present viewers with the scene beyond. For Merleau-Ponty, the relevance of pictorial perspective is that it is a means of arbitrating conflict (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 86). Comparing “free perception” or “spontaneous vision” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 86) to classical perspective he says:

Before [in spontaneous vision], I had the experience of a world of teeming, exclusive things which could be taken in only by means of a temporal cycle in which each gain was at the same time a loss. Now the inexhaustible being chrysalises into an ordered perspective within which backgrounds resign themselves to being only backgrounds (inaccessible and vague as proper), and objects in the foreground abandon something of their aggressiveness, order their inner lines according to the common law of the spectacle, and already prepare themselves to be backgrounds as soon as is necessary (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 87).

Throughout this essay, Merleau-Ponty provides evocative descriptions of spontaneous vision, many of which resonate with my experience of activities such as sketching Ginger in the park. He describes how, in normal vision (or free perception), “things [compete] for my glance; and anchored in one of them, I [feel] in it the solicitation of the others which made them coexist with the first – the demands of a horizon and its claim to exist” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 87). In other words, visually anchored in a thing, I am continually compelled shift my attention and, visually anchored in the next thing, the first is still somehow present.

But when drawing in perspective, “what I transfer to paper is not this coexistence of perceived things as rivals in my field of vision. I find [instead] the means of arbitrating their conflict” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 86). Adhering to the conventions of perspective, “The whole scene is in the mode of the completed or of eternity ... Things no longer call upon me to answer and I am no longer compromised by them” [emphasis added] (Merleau-Ponty, 1993b, p. 87). For Merleau-Ponty, perspective is a way of imposing order on things and fixing them in place and, in this sense, it is like Heidegger’s descriptions of Enframing and reducing things to objects.

In 3D animation perspective projection is automatic and it is just one of many ways in which the software arbitrates conflict. Merleau-Ponty notices that in spontaneous vision, things call upon us to answer, which means that things move us physically and emotionally. Merleau-Ponty also insists that in free perception things are ambiguous and invite a variety of interpretations; in free perception things are vaguely unsettling. But for a 3D user, objects and scenes are usually unambiguous and don’t call upon us to answer.

Given the numerous ways that 3D software quietly arbitrates conflict, how can a 3D user explore spontaneous vision?

Franck describes how he is physically moved by ordinary things, always seeing them as extraordinary, while Cézanne’s work is motivated by a “feeling of strangeness” (Merleau-Ponty, 1993a, p. 68). Both of these artists work from life and are continually intrigued by things that are usually taken for granted. Working with predesigned digital objects (including automatic perspective projection, algorithmic lighting models and mesh creation tools such as a Paint Effects tree), the 3D user seldom interrogates their own perceptual experience and easily takes the perceived world for granted, often blindly accepting representational conventions.

Merleau-Ponty urges us to bring the world of perception “back to life”, and warns that it is often “hidden from us beneath all the sediment of knowledge and social living” (Merleau-Ponty, 2004, p. 93). Similarly, the world of perception is hidden from 3D users beneath all the sediment of knowledge packaged as 3D tools and standard workflows.

In my attempt to shake up this sediment of knowledge and expand the language of 3D software, Merleau-Ponty’s thought, in conjunction with Monet, Cézanne and Franck, suggests the value of returning to the world of perception.

How can a 3D animator disrupt habitual ways of seeing and experience their own role in the constitution of things?

This is one of the questions explored in the next section of this document.

Things Themselves: Conclusion

At the conclusion of this section I am left with a number of questions, including the following. As a 3D animator, how can I move from challenging-forth to bringing-forth? How can I foster a comportment of active receptivity? In other words, how can I work with things without turning them into objects?

Following Husserl’s suggestions, what would it mean for a 3D user to begin in poverty? And, rather than simply using predesigned tools (where essences have already been defined), can a 3D animator gain something from seeing (and “fixing”) essences themselves?

Merleau-Ponty urges us to return to the world of perception but what sort of 3D practices could explore the role of the body in perceptual experience? As 3D animators, how can we incorporate our physical and emotional relation to things?

The answers to some of these questions are suggested by the work of other artists, including Bacon, Franck, Monet and Cézanne, as well as the work of digital artists such as O’Reilly, Hilleli and Menkman.

In the next section, I describe a practice-based enquiry which is informed by the considerations of phenomenology, and the various approaches adopted by the above artists.